By David L Ulin

Hanif Kureishi’s The Last Word suffers from the genius problem: To create a believable virtuoso, the character’s brilliance must light up the page. Such an issue arises any time an author tries to write about such a figure: J D Salinger, whose weakest effort, the novella Hapworth 16, 1924, is the only instalment in his Glass family saga written in the voice of the avatar-like Seymour, or Don DeLillo, whose Great Jones Street is roughest when it features the lyrics of the Dylanesque rock star Bucky Wunderlick.

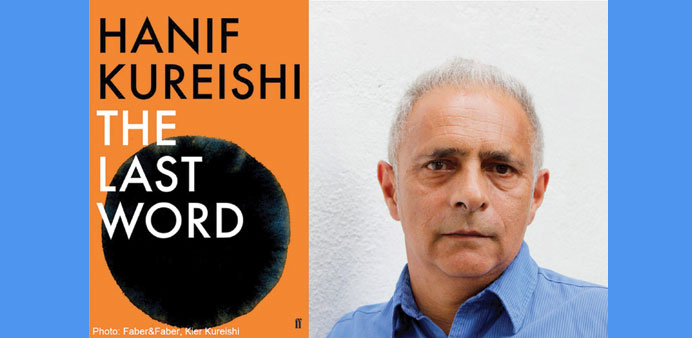

In Kureishi’s case, the genius is Mamoon Azam, an Indian-born great man of letters who late in life invites a young biographer named Harry Johnson to his English country estate. Mamoon is modelled to some extent on V S Naipaul — a reactionary, a bully, with unpopular ideas about immigration and race.

He is prone to pronouncements: “[W]e must bow down in gratitude to the fundamentalist,” he declares, “who reminds us how dangerous books and sex are.” He is if not predatory then seductive, toward both Harry, whom he alternately insults and flatters, and the women who have shared his life. These include his first wife, Peggy, dead of suicide; his current wife, Liana, frustrated but still protective; and a succession of infatuations including Harry’s fashionista girlfriend, Alice, pregnant with twins.

Still, the one thing Mamoon is not in The Last Word is a genius, at least not in any way we see. Or perhaps it’s more accurate to say that his genius is refracted, hovering in the background without ever quite asserting itself. To be fair, that’s part of the point; as Mamoon tells Harry, “You are now making an imaginary life. ... My life, as I have lived it, has been a Marx Brothers film, a series of detours, mistakes, misunderstandings, missed opportunities, delays, errors ... I am a man who never found his umbrella. Your life, I expect, is similar. ... Still, the idea of becoming a fiction does appeal.” What he’s getting at is the relationship between subject and biographer, the one condemned to existence, in all its three-dimensional elusiveness, and the other determined to find a narrative. Where does literature, does genius, fit in? Can it be accounted for at all?

“Nothing confuses like clarity,” Mamoon insists, defending the tendency toward the elliptical in his life and in his art. “The best stories are the open ones, those you don’t quite understand.”

For Kureishi, this is a matter of faith, aesthetic or otherwise. From the start of his career, he has willfully blurred lines of both genre and sensibility. His earliest success came as the screenwriter of My Beautiful Laundrette (1985), which portrayed London through the lens of social complication and forbidden love.

In 1990, he published his first novel, The Buddha of Suburbia, which evokes a similar vision, revolving around a teenager from South London with an English mother and an Indian father, who must navigate the overlapping minefields of family politics, infatuation, sexual orientation, racism and culture clash.

In these and subsequent works — the novels The Black Album and Intimacy; the screenplays Sammy and Rosie Get Laid and the magnificent Le Week-End — Kureishi relies on a loose, almost improvisational, approach to structure, and the sense that sex (or our inability to deal with it) is at the root of everything.

“All sex,” Mamoon tells Harry, “and indeed all pleasure, must include a poisonous drop of perversion, of devilish transgression — of evil, even — for it to be worth getting into bed for. It’s become banal, now that it is ubiquitous.”

At the heart of Mamoon’s statement is less conservatism than an odd form of nostalgia, a longing for a world with values, for better and for worse, that one can stand for or against. The challenge is that we do not live in such a world but rather one that has been “sucked toward the dirty stuff, a process of disillusionment. Unmasking was the thing. Leaving just bleached bones.”

Harry is a case in point: Although he claims to revere Mamoon as a writer, he is mostly interested in his excesses, his affairs. “Literature was a killing field,” Kureishi tells us, his own glee apparent; “no decent person had ever picked up a pen. Jack Nicholson in The Shining had the right approximation of a writer. If Harry showed merely a decent man rather than a mercenary, he wouldn’t be believed. No-one wanted that: it didn’t get anywhere near the hate, heat, and passion of a real artist.”

And yet this brings us back to the central problem of the novel, which is that we never see that heat, that hate. Instead, we get a series of set pieces, often played for broad effect. — Los Angeles Times/TNS