The most important discovery made by de Cardi and her team was the discovery of ‘Ubaid pottery from the 5th millennium BC, writes Fran Gillespie

Beatrice de Cardi, who celebrates her one hundredth birthday today, is the world’s oldest working archaeologist. She has become a legend in her time.

A lifetime of archaeology, much of it spent in the wilder and more inaccessible parts of Asia, sometimes involved adventurous and hardy travel in the style of other great British lady explorers such as Lady Anne Blunt, Gertrude Bell and Freya Stark.

An article published a few years ago in The Independent newspaper compared her to Indiana Jones. But de Cardi strongly dislikes the appellation. ‘I don’t resemble Indiana Jones,’ she declared firmly in an interview, ‘and I don’t like being compared to him because I want to project the image of an academic and not an explorer.’

Indeed, there is little resemblance to that swashbuckling adventurer in this elegantly dressed and immaculately coiffeured old lady, as she sits in her flat in Kensington, London, working on cataloguing pottery finds from some of the Gulf states.

Her links with the UAE, and particularly with Ras al-Khaimah, go back many decades: when the museum opened in 1987 the ruler presented her with the Al-Qasimi medal in recognition of her services to the state. She was the first woman to receive the award.

The quintessential independent British lady traveller, de Cardi ‘s origins are not British at all. Born in London, she was the daughter of a Corsican aristocrat and an American heiress of German origin.

She was educated at St Paul’s Girls School and University College London, and while there she attended some lectures by the famous archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler. As well as being a great archaeologist Wheeler was an inspiring lecturer, and had a particular gift for capturing the imagination of young people. Like many before and after her, de Cardi became ‘hooked’ on archaeology.

De Cardi joined Wheeler on a British excavation site, and from his wife Tessa she began to learn how to classify pottery, which had always been one of her main interests. She was offered a job by Wheeler as his secretary at the London Museum, where he was the Keeper.

Then came the war, and de Cardi found herself ‘lent’ to the Foreign Office who sent her out to China as a liaison officer. During this time, she visited India several times and decided she ‘rather liked it.’ She decided that after the war she would try and return there.

When the war was over she landed jobs in India and later in Pakistan with the UK Trade commission and was able to devote all her spare time to archaeology. She read an article by a young archaeologist, Stuart Piggott, who described some hitherto unknown painted pottery found on three sites near Quetta, the capital, since 1947, of Pakistan’s largest province Baluchistan.

Fascinated by Piggott’s account, de Cardi persuaded Mortimer Wheeler, who was now Director General of Archaeology in India, to let her go exploring in Baluchistan to try and find other sites with the distinctive pottery. Fearing for her safety, he rather reluctantly gave her permission and lent her the services of his foreman, Sadar Din, who had also worked with a British archaeologist from an earlier generation, Sir Leonard Woolley. It was this period of working in wild, untamed hill territory that led to the later fanciful comparisons with Indiana Jones.

In a BBC talk a few years ago, de Cardi paid tribute to Sadar Din. “I learnt more from him than from any books,” she said. “Sadar Din was a subordinate official of the Pakistani Archaeological Department and he was illiterate, but he had a marvellously retentive memory. He taught me what to look for and how to recognise it. When with him I found innumerable sites that other archaeologists had just passed by.”

“In those days,” she recalled, “English women didn’t really mix with what were then thought of as ‘subordinate’ members of society... there was a colour as well as a class distinction but I never felt it. If I liked a person and we got on, that was all that mattered.”

It was dangerous, bandit-infested territory, and at night in their tents they listened to the howls of wolves in the hills. Travelling in a clapped-out old jeep lent to her by Wheeler, she and Sadar Din located no fewer than 47 archaeological sites, a dozen of which had the distinctive pottery she named ‘Quetta ware.’ Some years later she was able to date it to the 4th/3rd millennium BC.

Political unrest in the region meant she was unable to return to Baluchistan for some years, and during this time she became the Assistant Secretary of the Council for British Archaeology, an organisation in which she still plays an active role.

In 1966, de Cardi returned to the East, to the western part of Baluchistan which forms part of Iran, and investigated sites along the Bampur River. She discovered some very distinctive grey pottery decorated with incised designs or with pictures of goats. It resembled some she recalling having seen in the Arab emirates, where a Danish expedition along with Geoffrey Bibby was excavating in Bahrain, Qatar, the UAE and eastern Saudi Arabia.

A visit to Bibby at Moesgard museum in Jutland, the home of the Danish expedition, soon confirmed it and a major discovery had been made: that there were trading links in the Arabian Gulf in the Bronze Age between what are now the Gulf states and the Indus Valley civilisation.

This discovery led to de Cardi coming to work in the Arabian Gulf region. She worked first of all in Ras al-Khaimah, where she and another British archaeologist conducted surveys and located a number of important sites including the pottery-producing area known as Julfar, and sites with Chinese Ming potsherds which confirmed that they had been occupied during the Portuguese period. She also discovered around 20 collective tombs dating to the 2nd millennium BC.

In 1973 Beatrice De Cardi arrived in Qatar. The government of Qatar was setting up the National Museum and had approached the British Museum for assistance in organising an archaeological expedition, and she was appointed as director.

“The archaeology of Qatar at that time was almost a total blank,” she said, “There was a gap extending from the Stone Age to the Oil Age: how might this be filled? I had just ten weeks to recover as much evidence as possible of Qatar’s past. In the ten weeks we carried out eight excavations and three regional surveys!”

The most important discovery made by de Cardi and her team in Qatar was the discovery of ‘Ubaid pottery from the 5th millennium BC, named after a site in Mesopotamia dug by Woolley in the 1930s. At Al-Da’asa on the west coast south of Dukhan several sherds of the ‘Ubaid painted greenish-buff ware were found, along with a small collection of stone and coral domestic tools, including a quern and graters, which had been carefully stashed, presumably by someone who intended to return and use them but never did so.

Similar fragments of painted pottery also turned up on sites on Ras Abrouq, including one near the film set, built a few years ago, of a traditional Arab town popularly known as ‘film city’.

All the evidence pointed to Qatar having formed trading links with other regions far longer ago than was once thought possible.

Although the British team only worked in Qatar for a single season, their work, carefully written up and illustrated and compiled and edited by de Cardi, resulted in the finest book on Qatar’s archaeology that has yet been published, the Qatar Archaeological Report published in 1978.

It was at this time that de Cardi suffered a great personal tragedy when her fiancé, who had been working with her in Qatar, died suddenly. The book is dedicated to him and a photograph of him appears in the front. She had lost her first fiancé when he was killed in World War II.

After Qatar, de Cardi continued to work in the UAE and Oman for many more years. More recently her excavations were of a ‘rescue’ nature, as rapid development and road building increasingly threatened ancient sites.

In Oman, on burial sites near Ibri, she discovered more of the grey Bampur ware that had first led her to realise that there was a trading link across the Gulf.

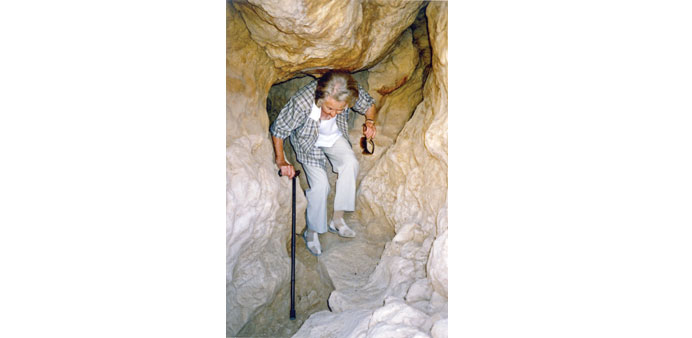

“I no longer excavate,” she explained in a BBC interview when she was 93, “because I can’t get in and out of trenches easily.” Instead, she continues to work on cataloguing pottery and on her writing. Unlike some archaeologists, de Cardi has always held a strong belief that excavations and research should be written up and published.

She is a regular attendee at conferences and archaeological gatherings in London, most recently at a meeting for the Council for British Archaeology in February this year, of which she is an Honorary Vice-President, and at the annual Seminar for Arabian Studies held at the British Museum, where she talks to archaeologists working in Qatar and the other Gulf states and keeps abreast of the latest discoveries. Despite what she herself refers to as her ‘staggering’ age, Beatrice de Cardi is more active than many people her junior, and her mind and curiosity ‘to know what’s around the next corner’ remains undimmed.