The risk of deflation in the US and the eurozone may require more expansionary monetary policy, such as quantitative easing (QE), QNB has said in a report.

Lower international commodity prices and subdued domestic demand have lead to historically very low inflation rates, well below the central banks’ target of 2%.

This calls for a continuation and possibly acceleration of unconventional monetary policy to offset the dangers that deflation could pose on an already weak recovery. The experience of Japan provides a useful historical precedent.

After decades of deflation and weak growth a successful mix of policies has helped Japan exit its deflations trap.

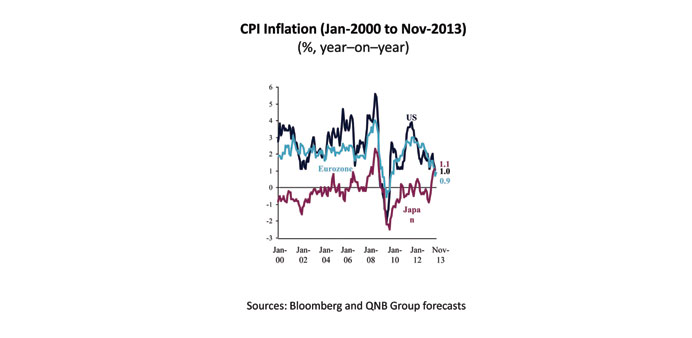

In October 2013, inflation in Japan rose above inflation in both the US and eurozone for the first time this century. Rising Japanese inflation is a direct consequence of expansionary economic policies introduced this year, which could help the country escape from the lost decades of low growth and deflation from the real estate crash of 1989 until today.

Meanwhile, inflation in the US and eurozone has fallen to around 1%, the lowest levels since 2009 when the global recession and collapsing commodity markets dragged down prices. These low inflation rates raise the risk that the US and the eurozone could be entering their own deflation trap with lost decades of low growth and deflation ahead, like in Japan.

According to QNB, this strengthens the case for an extension of expansionary economic policy, such as QE.

Since the 1990s, the Japanese economy has languished in a feeble state of weak growth and deflation that persisted into this century. From 2000 to May 2013, annual inflation of the consumer price index (CPI) was negative (averaging -0.3%), while real GDP growth was less than 1% over the same period.

However, in the last few months, the economy has turned around after a raft of expansionary economic policies was introduced by the current Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe, who came to power at the end of 2012. These policies, known as “Abenomics” include aggressive expansionary monetary policy, heavy spending on public infrastructure and an active policy to weaken the Japanese Yen.

Growth has averaged 3.1% so far this year and inflation rose from -0.3% in the year to May 2013 to 1.1% in the year to October. Abenomics is likely to have contributed significantly to Japan’s improving economic performance.

A consequence of expansionary monetary policy, such as QE, is that it tends to devalue the exchange rate by increasing the supply of money. This can have a positive impact on the economy as it makes a country’s businesses more competitive, encouraging growth. It can also push inflation higher by increasing the cost of imports.

Central banks tend to use monetary policy to target moderate annual inflation of around 2%, thus avoiding the perils of the deflationary trap.

Therefore, falling inflation in the US and eurozone, presents a strong case for the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank to further loosen monetary policy. This is particularly true in the eurozone, where growth averaged -0.7% in the first three quarters of 2013 and annual CPI inflation fell from 2.2% at the end of 2012 to 0.9% in the year to November 2013. At the same time the euro has appreciated 8.2% this year against a weighted basket of currencies, which is likely to be holding back inflation and growth. The ECB already cut its main policy rate from 0.5% to 0.25% in November, leaving little room for further interest rate cuts. Therefore, it is likely that the ECB will engage in unconventional monetary policies to provide stimulus by extending its long-term refinancing operations (LTROs), which provide unlimited liquidity to EU banks in exchange for collateral at low interest rates.

The ECB could also go a step further and stimulate the economy by purchasing government bonds directly in the primary market.

In the US, comments by Fed officials and minutes of the Fed’s Open Market Committee indicate that Fed governors are considering slowing the pace of $85bn monthly asset purchases, the so-called QE tapering.

However, according to QNB Group, slowing inflation could delay the start of QE tapering. The Fed is already likely to postpone tapering QE until early next year, once the political impasse over the budget and debt ceiling is resolved. If inflation continues to slow, QE tapering could take even longer to be implemented.

Overall in 2014, deflation could be a serious risk for the US and Europe, QNB said. “Continued expansionary monetary policy could therefore alleviate some of this risk as shown by the recent experience in Japan. It could also encourage capital flows to emerging markets, thus bring back some stability in global financial markets,” the report said.