|

|

The Cyprus financial crisis has had a “surprising impact” on the outlook for the eurozone and raised concerns about the euro, according to QNB Group.

Even though the country only accounts for 0.2% of eurozone GDP, Cyprus’ bailout has illustrated the need for further reform and has set dangerous precedents for future eurozone bailouts.

While optimism has prevailed so far in 2013, the escalation of the Cyprus situation could mark another turning point in the eurozone crisis and the beginning of the re-emergence of systemic tensions.

The two largest banks in Cyprus, the Bank of Cyprus (BoC) and the Cyprus Popular Bank (Laiki Bank) were both heavily impacted by the Greek financial crisis through exposures to their own operations in Greece and to Greek sovereign debt.

Following the second Greek bailout in 2012, both banks needed to be re-capitalised by the Cypriot government. They also tapped funds from the ECB’s Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA) to support increasing liquidity demands from operations in Greece. Laiki has drawn almost €10bn from the ELA.

In order to solve the critical situation of the country, the troika (the European Commission, ECB and IMF) entered into negotiations with Cyprus to address the shortfall in funding of the Cyprus government and banks, estimated to be €17bn.

Negotiations initially concluded on March 18, but the troika was only prepared to provide €10bn of emergency funding. Cyprus would raise the remainder itself with €6bn coming from a levy on deposits above and below the insurance ceiling of €100,000. In exchange for lost deposits, savers would receive equity stakes in their banks.

However, this deal was rejected by the Cypriot Parliament the next day.

In the final agreement reached on March 25, it was decided that Laiki Bank should be restructured with its good assets and insured deposits below €100,000 being transferred to BOC.

Whether uninsured deposits over €100,000 from Laiki Bank will be repaid will depend on the receivership process and the liquidation of bad assets.

Meanwhile, large deposits of over €100,000 in BOC have been frozen and may be subject to a haircut at a later date if it is deemed necessary to meet capital adequacy requirements. A significant portion of secured debt in BOC is also expected to be written off.

However, this package looks threatened following the recent news that €23bn in rescue funds are needed, meaning that Cyprus needs to find €13bn rather than €7bn in addition to the EU/IMF bailout of €10bn. It is now thought that the emergency measures put in place could raise around €11bn, leaving a shortfall of €2bn.

Although eurozone officials, including the president of the ECB, have clearly stated that Cyprus is a special case and does not provide a template for future bailouts, investors and savers remain acutely concerned that future bailouts could also involve a haircut for depositors in banks.

In savers’ minds, Cyprus may have set a precedent. It could encourage the removal of savings and deposits from banks in larger economies that look like they may require a bailout in the future. It could encourage capital flight from the eurozone and undermine the value of the single currency.

Following the bailout, Cyprus became the first ever eurozone country to apply capital controls with limits on credit card transactions, daily cash withdrawals, foreign money transfers and cashing cheques. This is a clear indication of the severity of the situation and, effectively, at least temporarily devalues Euros located in Cyprus as they are now less easy to transfer.

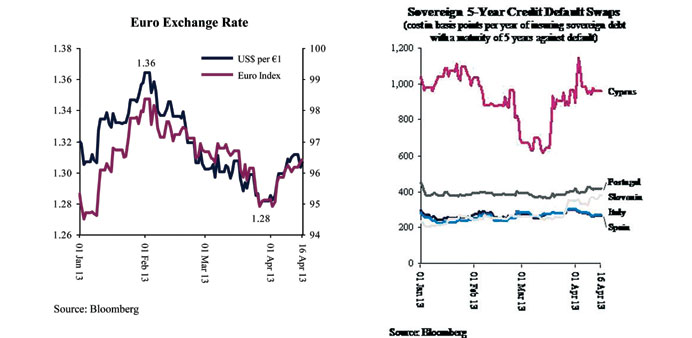

The Cyprus crisis has already helped drive the value of the euro down from $1.36 at the beginning of February to $1.28 at the end of March, QNB said. This is partly owing to a general strengthening of the dollar, but the euro has depreciated against most major currencies and Bloomberg’s euro index has dropped 3.5% over the same time period.

Furthermore, the botched initial bailout package has raised concern about the management of Europe’s financial crisis.

The issues faced in the Cyprus crisis are the same as those faced in previous bailouts. Over-indebted banks have been supported by the government until the sovereign itself has run out of funds to re-capitalise the banks and becomes insolvent.

It also illustrates how financial contagion is still occurring as Cypriot banks were negatively impacted by their exposure to the Greek crisis. The re-occurrence of these issues suggests that Europe has failed to stem the spread of the crisis.