Countries are unlikely to compete to devalue their currencies and herald a new currency war despite global concerns following the sharp depreciation of the Japanese yen, the QNB Group has said in an analysis.

The sharp depreciation of the Japanese yen this year has contributed to growing concerns about the outbreak of an undeclared currency war. However, although loose monetary policies could spark further shifts in exchange rates, QNB does not expect that countries will compete to devalue their currencies.

Even if a currency war was to develop, the GCC (Gulf Co-operation Council) countries would be somewhat sheltered from the impact. If the dollar was to weaken (leading to similar depreciation of pegged currencies in the Gulf), then the price of oil would tend to increase, boosting hydrocarbon revenue and partly offsetting the impact of any increases in import costs on government finances and the balance of payments, QNB Group said.

Since 2008, when the global crisis led to a major drop in growth rates, there have been suspicions that countries might seek to boost exports by attempting to weaken their currencies.

A weaker currency enables a country to sell its exports more cheaply than competitors with stronger currencies; the US has long accused China of keeping its currency artificially weak for this reason. These concerns have been fed by unorthodox monetary policies pursued by many central banks to stimulate their economies, such as quantitative easing (QE), which involves central banks buying bonds.

The increase in money supply resulting from these bond purchases tends to cause depreciation against currencies with more constant supplies. This relationship was clearly demonstrated on February 20, when minutes from the monthly meetings of the committees responsible for setting monetary policy in the UK and US were released.

The UK minutes showed more support than expected for increasing QE purchases, and the British pound depreciated on the news. The US minutes, by contrast, suggested that its QE might be scaled back, leading to appreciation in the US dollar.

This partly explains why some countries which have not engaged in QE, such as Brazil, have seen their currencies appreciate in recent years. The strong Brazilian real has harmed exports and contributed to a sharp slowdown in its economic growth, leading to accusations against countries like the US that they are gaining an unfair trading advantage as a result of QE.

However, currency devaluation is generally a side-effect, rather than the intended consequence, of QE or other monetary easing measures, such as a lowering of central bank interest rates.

Instead, the purpose of QE is to boost domestic liquidity and bring down long-term interest rates, enabling businesses to borrow, expand and create jobs, QNB said.

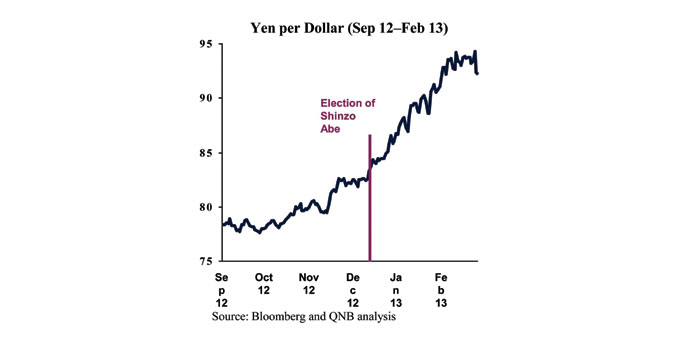

The currency debate intensified after the Japanese elections last December. The new Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe, initiated a major shift in monetary policy, which has caused the yen to depreciate sharply, losing about 14% of its value against the dollar since the start of December.

Abe has increased the central bank’s target rate of inflation from 1% to 2%, in order to enable a looser monetary. He is also nominating a new central bank governor more supportive of stimulus measures. The currency markets actually began to shift in advance, indeed even ahead of the election, in anticipation that Abe would be successful in implementing these polices.

The latest devaluation, to around ¥92 per dollar, returns the exchange rate to its early-2010 level. However, putting this in context, the yen had been appreciating during most of the previous five years, strengthening from 123 to the dollar to just 76 in early 2012.

This should help Japanese exporters versus the competitiveness challenges they faced when the yen was strong. As a result, it has led to sharp criticism from some of Japan’s trading competitors such as South Korea, QNB said.

After the yen, the British pound has been the worst performing currency this year, losing nearly 7% of its value against the dollar, partly because of its ongoing QE programme. The partial recovery of the euro, since its low point last July, has raised concerns about the competitiveness of European exports, which led France to talk about a more managed exchange rate policy. These are some of the warning signs of a potential currency war.

If countries were to begin actively competing to achieve the weakest exchange rate, then that would have very negative consequences. The most serious instance of this came in the 1930s when the US and UK ended their currency peg to gold, ushering a period of competitive devaluation that created price uncertainty for companies, harming global trade and intensifying the Great Depression.

However, according to QNB Group, the evidence so far suggests that the major countries are much more focused on using monetary tools to manage domestic demand than on influencing exports through exchange rates. Indeed, an analysis of countries’ macroeconomic profile suggest that Japan and the UK are among the countries least likely to benefit from currency devaluation, given their high levels of foreign currency debt (which becomes more expensive in the event of devaluation) and relatively low ratios of exports to GDP.

The issue was significant enough to make the agenda of the finance ministers of the G20 who met in Moscow on February 16. The G20 issued a statement pledging that its members would not engage in competitive devaluation, and significantly, did not criticise Japan’s recent actions.