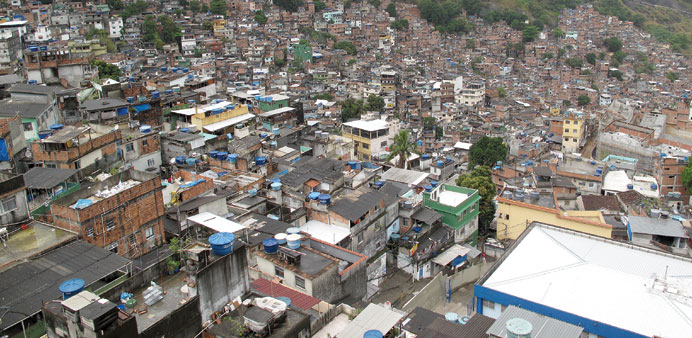

A Favela in Rio de Janiero: Slum tours are advertised by those who offer them as the ultimate way of getting closer to the way poor people live.

By Johanna Uchtmann

The black residents of Katutura, near the Namibian capital Windhoek, clapped and hollered as the white tourists cycled slowly through their township. Thinking they were witnessing a bicycle race — the riders all wore snow white helmets and neon yellow vests — they were trying to spur the apparently fatigued racers on.

And they were delighted that the only black person, KatuTours guide Anna Mafwila, was out in front. “Suddenly the roles were reversed and the tourists became the objects of observation,” said social geographer Malte Steinbrink of Mafwila’s description of her first tour of Katutura, which means “the place where we do not want to live.”

Steinbrink, who teaches at the University of Osnabrueck’s Institute of Geography and is a member of a research team on slum tourism in the Southern Hemisphere, approves of KatuTours’ approach but finds it difficult to judge the phenomenon of slum tourism as a whole.

Organised visits to squalid, usually overcrowded sections of cities by curious outsiders, sometimes called “slumming,” have been criticised as an exploitation of poverty for entertainment purposes.

“People often make the claim that it’s a kind of voyeurism similar to zoo visits,” Steinbrink remarked. But, he added, “is it better to look the other way? And what effects do moral qualms have on the way slum tourism is practiced?”

Steinbrink divides slum tour operators into three main categories. The first promises tourists the experience of a completely different culture and way of life. The second touts a donation of part of the proceeds towards the slum dwellers’ well-being. And the third says the tour will show how “the other half really lives.”

Slums are “backstage areas” of cities, Steinbrink said, and Westerners who travel there want to acquaint themselves with the “ultimate place of otherness. Experiencing the difference serves to establish and confirm their own identity.”

He noted that slum tours were seldom organised by slum dwellers themselves. Most of the slum tour operators in Namibia, he said, seemed to be people who also offer safaris.

One of them is Carsten Moehle. For 17 years, Katutura has been part of the programme at his tour company Bwana Tucke-Tucke. Up to seven tourists at a time ride in an open Land Rover through the township.

“At first a lot of guests were afraid it was too dangerous,” Moehle recalled. “It’s not, though. The inhabitants are very friendly.” Children often climb into the vehicle “and our guests then pass out ice cubes to them as a little refreshment.”

Moehle probably fits Steinbrink’s third category of tour operator, the one promising warts-and-all reality. “You rarely get closer to Africa,” the company website says of the tour.

Steinbrink is not enamoured with township kids hopping on vehicles. “The children are drawn in so that the tourists have something to photograph and cuddle,” he said.

For Julia Burgold at the University of Potsdam’s Institute of Geography, picture-taking is a no-no. Like Steinbrink, Burgold, who is writing a doctoral dissertation on slum tourism and has dealt mainly with the Dharavi slum in Mumbai, India, is loath to make a blanket judgement, however.

“It depends on how the tours are carried out,” she said.

Out of consideration for the inhabitants, Burgold said, slum tour guides should not only prohibit tourists from taking photographs but also go with them on foot rather than in SUVs or, even worse, buses.

Slum tourists on foot who do take pictures should be sensitive to the inhabitants’ dignity and not “unrestrainedly point their cameras at people’s faces,” Steinbrink advised.

According to Burgold, tour groups should not be too large. “Twenty participants are quite a lot,” she said. “It’s best if the number is less than 10.”

Having slum dwellers as guides is also a good idea, she added. This creates jobs for them and makes them active participants instead of passive objects of tourism. In Burgold’s view, tour operators would also do well to support charitable projects in the slum and be transparent about where ticket revenues go.

Steinbrink has seen many slums over the years and the extent to which slum tourism has changed. “The market is really booming,” he remarked. Every year, he pointed out, one or two more cities worldwide start offering slum tours, and over a million people annually take part in such tours.

There are now slum tours involving quad bikes, music, paintball games and even bungee jumping, for example in the black urban complex of Soweto, adjacent to Johannesburg, South Africa. “That’s actually quite apt,” Steinbrink said. “Slum tourism is, after all, a kind of social bungee jumping.” – DPA