For many bond investors it’s a matter of when, not if, Lebanon restructures its $87bn of debt as it reels under a deepening financial crisis. Working out what the trigger would be or the extent of the fallout is another matter entirely.

After repaying $1.5bn Eurobonds that matured last month, the focus is turning to whether authorities will honour a $1.2bn commitment on March 9. Several influential local economists and even some officials say the country should use its dwindling reserves to pay for imports instead of creditors.

Complicating the debate is the nation’s political paralysis since mass protests against corruption forced the prime minister to resign in late October. The country’s debt risk, measured by five year credit-default swaps, climbed above 2,500 basis points last week and is the highest globally after Argentina, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

As politicians haggle over the formation of a new government, some creditors and distressed debt funds have been asking for documents detailing payment terms, including what would happen in the event of a default, according to a person with knowledge of the matter. Government officials are aware of the requests, said the person, who asked not to be identified because the matter is sensitive.

“The market is running out of patience,” said Anders Faergemann, a London-based money manager at Pinebridge Investments, which holds an underweight position in Lebanese bonds relative to the benchmark it follows. “Until investors know who will be in control of the country’s finances, it will be hard for the market to recover.”

Here’s how the saga could unfold:

The quick fix

Few expect it, but Lebanon could avert financial ruin by quickly forming a government that would pledge immediate reforms and receive aid from international allies.

France was hosting a support conference in Paris on Wednesday. And while donor nations are unlikely to extend a blank check without a functioning government, diplomats fear a messy default would wreak havoc on a country at the heart of proxy wars in the Middle East.

Some critics, however, would see this outcome as an easy way out for a political establishment that mismanaged the economy and stymied efforts to end corruption.

Sharing the pain

For caretaker Labour Minister Camille Abousleiman, the new government should announce a restructuring before the March Eurobond is due, accompanied by a reform programme that’s preferably backed by a loan from the International Monetary Fund.

“We do not want to end up like Venezuela, where priority was given to creditors at the expense of basic needs,” said Abousleiman, who has acted as principal lawyer for Lebanon’s Eurobond issuance since 1995.

In Venezuela, the population suffered from shortages of goods including medicine, yet the government ended up defaulting anyway in 2017.

Supporters of this solution say it would help minimise the damage inflicted on creditors, domestic banks and depositors. Economic proposals floated locally include reforming the loss-making state-owned electricity company, official capital controls instead of the informal limits imposed by banks, higher taxes on the rich and a cap on interest rates.

Any revamp of Lebanon’s almost $30bn of Eurobonds would require the consent of 75% of holders voting on a series-by-series basis, Abousleiman said.

Keep it local

The government could limit the restructuring to its local-currency debt held by the central bank, domestic lenders and other public institutions. Local debt stood at 81tn Lebanese pounds ($54bn) as of September, with the central bank holding about 65% of the total.

That plan would spare foreign investors and might be done in a way that avoids substantially damaging the balance sheets of local banks.

Muddle through

“We have a high conviction about the March bond being paid, but it’s no bargain given risks,” analysts at Oxford Economics, including London-based Nafez Zouk and Carlos de Sousa, said in a December 3 report. “We think the status quo of ‘pay while you can’ will prevail because it presents the way of least resistance for policy makers.”

The price on the March bond fell to a record low of 77 cents last month, equating to a yield of more than 100%. It has since risen to 86 cents.

A senior local banker, who asked not to be named, said this scenario could be introduced hand-in-hand with official capital controls and an economic reform blueprint that would slash the budget deficit.

Lebanon probably has enough reserves to “muddle through” for more than a year and there’s a chance that external debt isn’t touched even after that, said Hans Humes, chief executive officer of the New York-based distressed-debt investor Greylock Capital Management LLC.

The risk: Surviving to default another day.

The mess

A disorderly default would shut the country out of international debt markets, potentially for years. What’s worse, a collapse of the banking system could fuel unrest in a country that’s no stranger to turmoil. So far politicians have no clear picture of what a future government would look like.

Two candidates have publicly withdrawn their nomination for the premiership and others have implicitly declined it.

Lebanon’s dollar debt, most of which trades at less than 50 cents, isn’t yet cheap enough to interest Humes. That might change if a government isn’t put in place soon, which could cause prices to drop further.

“The uncertainty of the situation has led to discussions among creditors to begin some preliminary discussions on how to organise,” Humes said. “We recognise the uniqueness of Lebanon’s situation.”

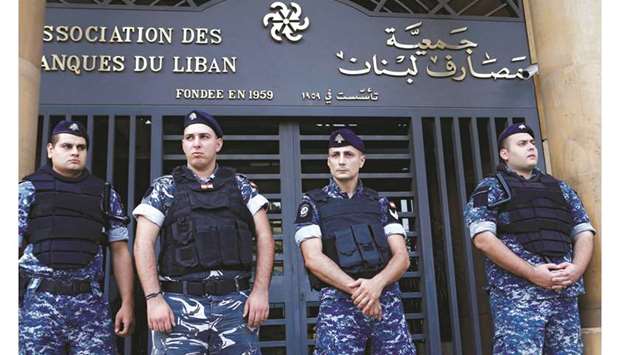

Lebanese police stand outside the entrance to the Association of Banks in downtown Beirut (file). After repaying $1.5bn Eurobonds that matured last month, the focus is turning to whether authorities will honour a $1.2bn commitment on March 9. Several influential local economists and even some officials say the country should use its dwindling reserves to pay for imports instead of creditors.