Tunisia expects its economy to turn a corner by 2020, Prime Minister Youssef Chahed has said, as his administration faces a wave of protests over living standards that have been slow to improve since the Arab Spring revolution of 2011.

The government is working to reduce spending, revive exports and introduce social measures to meet the concerns of anti-austerity demonstrators, Chahed said in a recent interview in Marrakesh.

“We succeeded in implementing this new democracy – however we were not really successful in implementing and succeeding at the economic level,” he said. “The challenge now is about the economy, how to recover the economy, how to increase the growth level in order to create jobs, that’s the number one challenge for us.”

Often hailed as the lone success story in the uprisings that swept the Middle East in 2011, tiny Tunisia has navigated the fraught road from dictatorship to democracy that has thrown some neighbours into chaos. But political freedom has come with a steep economic price tag.

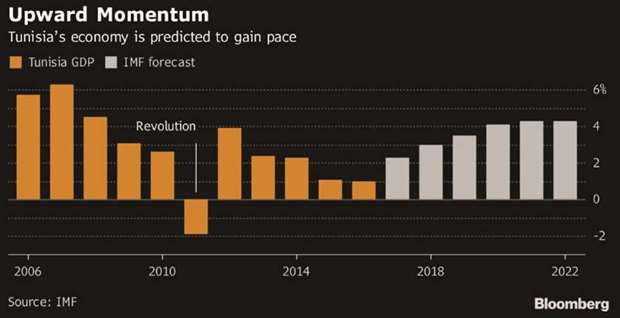

Growth slowed from more than 5% before the revolution to barely 1% amid repeated strikes and protests by Tunisians demanding the fruit of their uprising. Tunisia has had seven governments since the ouster of Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali. Economic output bounced back to 2% in 2017, as the tourism industry began to recover after a series of terrorist attacks, and the government embarked on International Monetary Fund-backed reforms to cut the budget deficit and boost competitiveness.

Violent protests erupted last month against the government’s programme of subsidy cuts and tax increases. The demonstrations subsided after the government offered about $70mn to help low-income households weather the price increases.

If Tunisia can stay the course on reforms and barring major terrorist attacks, Chahed said he expects growth to reach 3% this year and return to pre-revolutionary levels by 2020.

In Tunisia’s favour, has been the sympathy and support it has received from international lenders and donors reluctant to abandon North Africa’s nascent democracy.

Tunisia has missed some of the targets set when it agreed a $2.9bn IMF programme in 2016, but support has rarely wavered. IMF chief Christine Lagarde last week said the international lender would back Tunisia’s efforts to make its reforms more socially balanced as it addresses public anger.

“We are trying to reduce the budget deficit, a very important challenge, so any mechanism or any innovation helping Tunisia is really helpful,” Chahed said.

Tunisia’s key tourism sector was devastated by a series of terrorist attacks in 2015, which prompted several flight bans and forced the government to ratchet up security spending to about 15% of the budget. Most travel restrictions have been lifted.

The country has also introduced more flexibility into its exchange rate regime, allowing the dinar to depreciate, boosting competitiveness for tourists, trade partners and foreign investors. Chahed now aims to increase the country’s exports by an annual 20% through 2020.

The government is also working on extending health coverage to the unemployed, guaranteeing a minimum income for the poor, and providing more social housing, he said.

Headline growth numbers don’t tell the whole story, Chahed said. “We had 5% growth before the revolution – so it’s not enough,” he said. “This economic growth has to be more job- creative.”

.