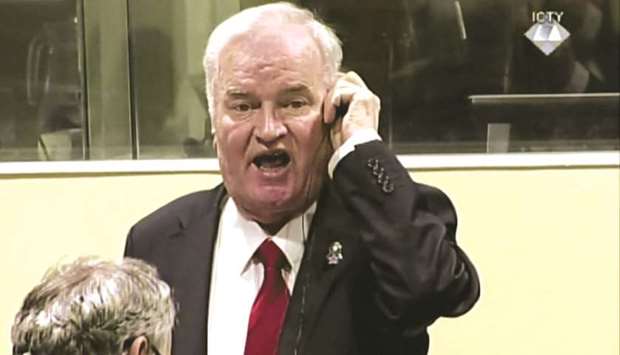

The sight of a judge in The Hague interrupted by insults and obscenities from Ratko Mladi? as the court convicted the former general of genocide reached us like the light of a distant star. The jailing of the butcher of Srebrenica happened recently, but it gave off the glow of a spark lit more than two decades ago. It’s not just that Mladi?’s crimes were committed in the mid-1990s. It’s that the very idea of bringing war criminals to justice seems like a memory from the distant past.

The day before Mladi? was taken to the cells, Robert Mugabe resigned from the Zimbabwean presidency he had held for 37 years, reportedly in return for keeping shut the files that detailed his culpability over the massacre of 20,000 or more people in Matabeleland in the early 1980s. Even the longtime opposition leader, Morgan Tsvangirai, famously beaten at the hands of Mugabe’s henchmen, said the dictator should not face justice. “To pursue the old man will be a futile exercise,” he told BBC Newsnight. “I think let him go and rest his last days.”

Tsvangirai was doubtless bowing to the political reality that Mugabe has been replaced by his own ruling party, which has no interest in exhuming its recent history, and to the enduring fact that societies riven by conflict often have to forfeit justice over the past for the sake of peace in the future.

But there are other peoples who stand to be similarly denied justice, with no compensating prospect of peace. More than 620,000 Rohingya people have fled Myanmar for Bangladesh to escape ethnic cleansing so horrific it shocks even the most hardened observers.

“Survivors said they saw government soldiers stabbing babies, cutting off boys’ heads, gang-raping girls, shooting 40-millimetre grenades into houses, burning entire families to death, and rounding up dozens of unarmed male villagers and summarily executing them,” the New York Times reported last month.

Meanwhile, civilian blood is shed every day in Yemen, by the Saudi-led coalition; and in Syria, at the hands of the Assad regime and what remains of ISIS. Who would bet on the perpetrators of those crimes ever standing in a dock?

On the contrary, not only is the “international community” doing little to stop the killing: it is actively undermining any future chance of prosecuting the guilty. Last week Russia used its security council veto to shut down UN inspectors in Syria who had been gathering evidence of chemical weapons use. At the same time, the Commission for International Justice and Accountability, a small but widely admired NGO similarly engaged in crucial evidence-collection in Syria, has had its US government funding cut off – perhaps as the precursor to a US-Russia deal that allows Assad to get away scot-free having slaughtered hundreds of thousands. How has this happened? How did a world that decreed in 1945 that “never again” would genocide go unpunished, that in 1945 designed a new legal architecture for crimes against humanity, whose foundations were laid at the Nuremberg trials, find itself 72 years later shrugging in the face of such atrocity?

The first fact to remember is that, for all that Nuremberg was a revolutionary breakthrough, there was nothing like it for another 50 years. Then, in the 1990s, came international tribunals on the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda – acts of contrition after the horror, to make up for the global failure to prevent it – and the establishment of the international criminal court. Put another way, when you assess the postwar era as a whole, the prosecution that saw Mladi? jailed recently emerges as the exception, not the rule.

And that exception came out of a very specific confluence of circumstances, one not easily repeated. In the 1990s, after the end of the cold war, Russia was so weakened that it gave its blessing to the kind of concerted action that today it would veto. (Among Mladi?’s shouted courtroom insults was his insistence that The Hague was nothing more than a “Nato court”: were such a tribunal proposed today, Vladimir Putin would surely say the same.)

What’s more, the 1990s saw what seemed to be an epochal shift in the reach of international law. The founding of those tribunals and the ICC, coupled with the arrest in London of the Chilean ex-dictator Augusto Pinochet, suggested a new world was emerging, one in which national sovereignty was no longer sacrosanct. No longer would tyrants be able to brutalise or murder their own people with impunity.

According to the international lawyer Philippe Sands, that more hopeful model of international justice “has stalled”. Witness the fact that the ICC is not dealing with the major crimes of the age: Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, ISIS, Zimbabwe, Yemen and Myanmar are all absent from its docket.

Responsibility lies chiefly, says Sands, with the two countries that drove through that shift in the 1990s, the same two countries that insisted on the rule of law and due process in 1945: the US and the UK. When it comes to international justice, both have “taken their foot off the pedal”. British disengagement found its perfect symbolic expression this week, when a UN vote meant that, for the first time since its founding in 1922, there will be no British judge on the international court of justice.

It would be tempting to blame this decline on Brexit or Trump, but in truth it pre-dates them both. The US refused to ratify the ICC from the start, while the British turn inward can perhaps be traced back to the Iraq calamity of 2003. After that, military intervention against murderous foreign regimes became discredited – and yet, as the Nuremberg and Yugoslavia tribunals illustrate, often it takes a wholesale military defeat to get the likes of Mladi? into court.

What can be done to revive the notion that lethal dictators should face justice? It might require reform of the key international institutions to make them legitimate again. It hasn’t escaped the developing nations’ notice that only Africans have ever been indicted by the ICC. A change in the permanent membership of the UN security council, still tilted towards Europe and the west, might help.

More deeply, we might need to renew an argument that these days looks forlorn. It is the view that there are, and should be, limits on national sovereignty – that no tyrant has the right to kill with impunity, even within his own borders. In this current era of surging nationalism and populism, when sharing sovereignty and supranational institutions are both desperately unfashionable, that will seem a lost cause. Justice is like that. It often seems hopeless – but we must pursue it all the same. - Guardian News & Media

* Jonathan Freedland is a Guardian columnist

‘Ratko Mladi? shouted insults and obscenities as the court convicted the former general of genocide.’