There is an ongoing trend in countries with Islamic finance ecosystems of discovering the importance of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) for economic well-being and growth.

Traditionally, SMEs have not played a substantial role in oil-rich Middle Eastern countries where the economy used to be dominated by large family enterprises, and financing for small businesses was hard to come by. Neither was is easy for SMEs in other Muslim countries, namely in the developing world, to become eligible for loans despite the general insight of governments and economists that SMEs are basically the lifeblood of domestic economies, from Malaysia, Indonesia, Bangladesh to Egypt, Pakistan, Turkey and North and Sub-Saharan Africa.

In fact, SMEs in developing countries represent the majority of employment opportunities, particularly for female employment, which makes investing in SMEs a macro-economically wise strategy.

As a rule of thumb, small enterprises have up to 50 employees, medium-sized enterprises have up to 250 employees, while micro-enterprises are defined having up to ten employees. Globally, SMEs make up over 95% of all firms, account for approximately 50% of the world’s GDP and up to 70% of total employment in both formal and informal sectors. Estimations are that there exist more than 500mn SMEs around the world, of which over 300mn are in emerging markets and roughly a third of those in Muslim countries.

This makes a clear case for Islamic financial institutions and jurisdictions to support SMEs. Even more so, as SMEs keep struggling to gain reliable access to capital, with an estimated 68% of SMEs in developing countries being financially underserved or not served at all, according to the International Finance Corp (IFC), an organisation of the World Bank focusing on private-sector development in developing countries.

The IFC further estimates that SMEs and micro-enterprises across the Middle East and North Africa region alone are in need of up to $13.2bn in Islamic financing. It is estimated that an average about 32% of SMEs across this region are totally excluded from access to finance, with absolute numbers varying from country to country. For example, Shariah-compliant loans for SMEs represent only 7% of total loans in Egypt, whereas the demand for Islamic financial products is about 20% in the country. Saudi Arabia, in turn, is able to supply 67% of the overall demand of 90% owing to its large number of Islamic banks.

Customarily, Islamic banks have tried to avoid the risk of financing SMEs and micro-enterprises because they were seen as inherently “unbankable” because they were operating in informal sectors of the economy or would otherwise not qualify for loans due to a lack of managerial capabilities, visceral operation structures, absence of risk management, opaque bookkeeping or a general lack of understanding of Shariah-compliant financing structures.

This has led to reduced capabilities of Islamic banks to lend to the SME sector and to an only narrow product range offered to SMEs in most countries. However, Islamic organizations have realized that if SMEs do not have access to finance, the sector cannot develop which is why, for example, the Organization of Islamic Co-operation has defined SMEs as its main target to “develop appropriate policies to accelerate the convergence between Islamic finance and SME industries,” particularly to promote the utilisation of Islamic finance products linked to “real economic activities.”

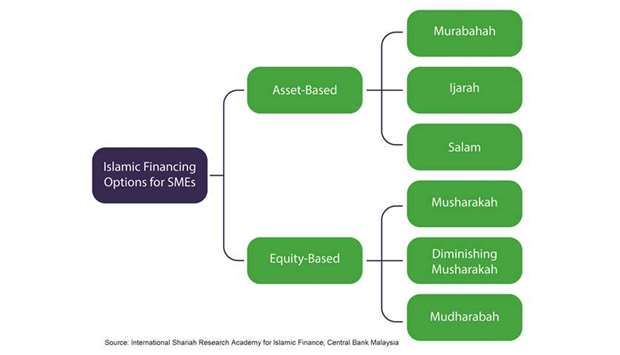

In fact, there are a number of asset- as well as equity-based Islamic financing options for SMEs, which include murabaha (credit sale), mudaraba (profit-loss sharing), ijara (leasing), musharaka (business partnership and salam (deferred delivery or sales contract). Islamic banks used to prefer, if at all, offering SME financing in the form of murabaha for its easy and less risky structure, thus it is crucial that new financing products for SMEs are being designed involving the other mentioned Shariah-compliant structures.

In order to achieve that, most Islamic jurisdictions are meanwhile eager to create an enabling environment for Islamic SME financing, including the adaption of financial regulations that take into account the defining features of Islamic finance and do not disadvantage Islamic over conventional banks by setting competitive tax and accounting standards, as well as by encouraging risk-sharing financing and strengthening information about creditworthiness of SMEs.

Some of these initiatives are expected to be led by the Islamic finance players themselves, while others will need to come from regulators ensuring that adequate credit risk systems are in place, with development banks partnering with Islamic banks to improve SME financing and capacity building, and with governments fostering financial education and literacy.

Notably, there have been a couple of achievements in this regard in the recent past. For instance, the UAE put into force a mini-insolvency law which turned out to have given the SME sector a boost, and Saudi Arabia last year launched a stock exchange exclusively for SMEs where they can raise funds by selling shares to investors and Islamic financial institutions. The Egyptian government encouraged the domestic banking sector to provide $25bn to fund SMEs in a move to support the country’s sluggish economy and create more jobs, while the Central Bank of West African States, which oversees the CFA franc zone in eight West African countries, has signed an agreement with the private sector arm of the Islamic Development Bank to help finance SMEs through a $100mn Islamic fund.

In Europe, the Bank of London and the Middle East, one of the UK’s five Islamic banks, acquired Renaissance Asset Finance, a specialist lender to the SME market, to bolster its leasing business by providing $45.6mn in Shariah-compliant SME financing. More initiatives are expected to follow as Islamic economies continue to embrace the SME sector in a move to recover economic damage after the 2014 oil price crash and the subsequent economic challenges.

isl