The year 2017 is seen to bring a rebound for sukuk after a slump during 2015 and 2016, international analysts say. While issuances of Islamic bonds were clearly subdued in the past two years, activity is expected to return as governments, particularly in the Middle East, seek to strengthen their budgets and at the same time aim at riding the growth wave of the entire Islamic finance industry as opposed to 2015 and 2016 when they mostly sought to balance their oil price-pressured budgets through the quick issuance of short-term conventional bonds.

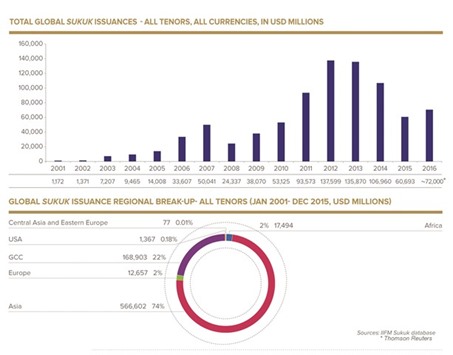

Looking back, from 2012 to 2014, sukuk issuances exceeded more than $100bn a year, with the 2012 figure of close to $150bn having been the highest in the period. However, 2015 witnessed a major drop in issuances when only $60.6bn of sukuk were issued, a massive 43% fall compared to 2014. The following year 2016 saw sukuk issuances worth about $72bn.

While increasing issuances were observed in US dollar, Indonesian rupiah and Pakistani rupee, decreases occurred in Malaysian ringgit, the internationally dominating sukuk currency aside the US dollar, as well as in Bangladesh taka compared to the year ahead.

In 2017, issuance are expected to rebound to between $ 75bn and $100bn, according to a Thomson Reuters forecast, mainly as a result of a macroeconomic mixture of a recovery in oil prices, more general investor demand in Islamic finance market, particularly from banks that need high-grade Shariah-compliant bonds to meet tightening liquidity standards, as well as subsiding apprehension over expected global interest hikes.

Most of all, expectations are that many oil and gas exporting countries in core markets will turn back to sukuk as a primary debt tool in 2017 to help improve liquidity instead of conventional bonds as in 2016 and 2015, namely the UAE, Qatar and Saudi Arabia.

“Last year, expectations were set on governments of oil exporting countries, mainly in the Gulf Cooperation Council countries, increasing their sukuk issuances to cover their widening budget deficits that resulted from persistently low oil prices,” says Nadim Najjar, Managing Director, Middle East & North Africa at Thomson Reuters. “However, these expectations were curbed. Although these governments increased their overall debt issuance, these were mostly geared towards conventional bonds.”

The reason behind that was that, as oil prices dropped, governments sought to raise money quickly on the international finance market through short-term debt and did not want to lose time by designing complex sovereign long-tenor sukuk.

Apart from the improving macroeconomic situation, there are also a number of new players entering the stage, which include North African, sub-Saharan African and Central Asian countries. For example, Morocco will be issuing its first sovereign sukuk before the end of 2017, according to Moroccan Economic and Finance Minister Mohammed Boussaid.

“These financial instruments should contribute to the development of participative banking, allowing the mobilisation of funds as needed,” Boussaid said at a symposium on Islamic Economics and Finance held last December in Rabat.

Signs are that the expansion of the sukuk market will continue elsewhere in Africa. Last year, Ivory Coast issued its second sukuk after a first one in 2015, and Togo and Senegal issued debut sukuk while countries such as Nigeria and Kenya are preparing to do so after creating a regulatory framework for Islamic bond issuances. Other sub-Saharan markets, notably in West Africa, are keen on following the trend.

In Central Asia, several governments are busy with fine-tuning Islamic finance regulations to issue Islamic bonds, while Turkey and Pakistan are expected to further increase their global share in the sukuk market. Iran is also likely to play a bigger role, but probably at a later point of time.

In Southeast Asia, Malaysia, one of the largest sukuk issuers globally, is expected to boost sukuk issuance as its economy improves, while Indonesia’s government is also seeking to tap more Islamic finance-related sources of liquidity.

In the GCC, Saudi Arabia should turn back to the issuance of long-term sukuk in the first quarter of 2017. In the West, the rising popularity of Islamic finance could bring more sukuk issuances from corporations in the UK, Luxembourg and, probably, in the US where a marked rise of Islamic financial institutions ranging from small community banks in the Midwest to nationwide investment banks and brokerage firms along the country’s financial high streets can be witnessed. In a first move, a Michigan-based community bank last April announced it is planning a debut sale of Islamic bonds.

.