By Steff Gaulter

The storm season in the Pacific has woken up. Suddenly storms seem to be sprouting up all over the place. In the last few weeks hurricanes have been swirling around Hawaii and a typhoon has hurtled towards Japan.

There is absolutely no difference between a hurricane and a typhoon. They are exactly the same thing, but different parts of the world give them different names; to the east of the International Dateline, these tropical systems are called hurricanes, and to the west, they’re called typhoons. Sometimes a storm can even change its name as it moves around the globe.

Earlier this month, Genevieve became the latest storm to endure a name change. A tropical system originated to the west of the Americas, and when the winds increased to more than 119 kph (74 mph), the storm became known as Hurricane Genevieve. The storm tracked westwards, well to the south of Hawaii, and crossed the International Dateline. At this point it changed its name, from Hurricane Genevieve to Typhoon Genevieve.

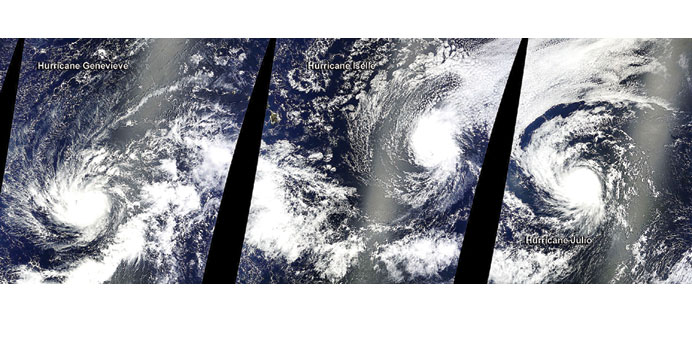

Genevieve was an interesting storm, and thankfully it never hit land. However, the conditions in the atmosphere in the area west of the Americas were just right for the generation of storms, so it wasn’t the only storm to develop. Two other systems developed in quick succession, strengthening into hurricanes named Iselle and Julio. These two followed behind Genevieve, but tracked slightly further north, putting them on a collision course with Hawaii.

Hawaii is a tiny archipelago in the middle of the Pacific. It is unprotected by any landmass, so you might think that it must get battered regularly by tropical systems. The strange thing is that it doesn’t. The last time that it was hit by a hurricane was in 1992, and the islands have only been struck three times since 1950.

This month it seems that luck was on their side again. Just 24 hours before Iselle made landfall, both Iselle and Julio were dangerous hurricanes. Iselle was the weaker of the two, only classed as a category one storm on the five-point Saffir-Simpson scale that rates hurricanes. However, following Iselle was Julio, a powerful category three storm, with sustained winds of over 178 kph (111 mph).

As the storms raced towards Hawaii, they began to lose intensity. Just hours before Iselle made landfall on the Big Island, the winds dropped below 119 kph (74 mph). This meant the storm was no longer a hurricane, but instead was a tropical storm.

Despite this, there was still a fair amount of damage caused by Iselle; the winds dragged down power-lines, leaving over 30,000 people without power whilst falling trees damaged homes and blocked roads.

Fortunately there was less damage than there might have been, because people had prepared for a hurricane, rather than a weaker tropical storm. This meant people had taken extra precautions, boarding up shops and taping up windows, neither of which is usually done for a tropical storm.

Just 48 hours after Iselle made landfall, Julio neared the islands. However, this hurricane weakened to a category one storm, and stayed to the north of Hawaii. The only warning in force as the storm reached its closest point to the archipelago, was for large surf for northern and eastern shores of Hawaii. Watching these hurricanes disintegrate as they approached Hawaii makes you wonder if an invisible force is protecting the islands. In a certain respect, there is.

There are two main conditions that need to be met if a storm is to intensify or to maintain its strength. Firstly, a storm needs the surface water of the sea to be 27C. This is because the energy source of tropical systems is the warm waters of the ocean. Secondly, a storm needs the winds to be of the same strength and direction throughout the atmosphere. This is known as low ‘wind sheer’, and this ensures that a system isn’t disrupted as it grows vertically throughout the atmosphere.

The reason that the islands seem to repel storms is nothing to do with the temperature of the surrounding waters, they are plenty warm enough to maintain the strength of a hurricane. Instead, the winds act as the protective shield.

High up in the atmosphere above Hawaii the winds usually blow from the southwest at around 65 to 95 kph (40 to 60 mph). This is completely different from the winds in the lower part of the atmosphere which generally tend to blow from the northeast. This means that any storms that approach the islands tends to be ‘blown over’, causing them to weaken or disintegrate altogether.

The time that the islands are most vulnerable to hurricanes is during an El Nino year, when the surface water of the Pacific is slightly warmer than usual. In an El Nino year, the strong winds high up in the atmosphere tend to drift away towards the north. Then, if the winds nearer the sea become southwesterly, the winds can become similar enough throughout the atmosphere for hurricanes to maintain their strength.

This is what happened last time that a hurricane slammed into Hawaii. In 1992, Hurricane Iniki formed to the southwest of the archipelago and strengthened dramatically as it bore down on the islands. By the time it made landfall on the island of Kauai, it was a powerful category four storm, with sustained winds over 209 kph (156 mph).

There is a chance that El Nino may develop in the next six months. If this happens, then there is a chance that the islands may have to prepare for a storm that is far more powerful than Iselle, but for the time being, Hawaii can continue to be the paradise islands for which they are famous.